NOAA ship Shimada track for 2/16/12

Last update — 3/2/2012, 10:00

Brad Hanson and his colleagues from the Northwest Fisheries Science Center, including Marla Holt and Dawn Noren, embarked today (2/16/12) from Newport, OR, aboard the NOAA ship Shimada (MMSI 369970147) to search for southern resident killer whales (SRKWs) along the outer coast of Oregon and Washington, and possibly California and British Columbia. With luck, they will encounter members of J, K, or L pod over the next 3 weeks and be able to gather further information about the wintertime habitat and behaviors of these salmon-seeking orcas that frequent the Salish Sea during the summer. It’s also possible they may learn more about what may have caused the death of L-112 who washed up at Long Beach (top of ship track map) on 2/11/12.

NPR offered a 1-minute prospectus for the cruise on 2/10/12, but it did not mention satellite tagging. Instead it only indicated the normal activities would take place — towing hydrophones to listen for calls, whistles, and clicks, and scanning for whales visually with binoculars from the ship’s bridge. In past winter cruises, they have deployed a small boat upon locating SRKWs to gather fecal and prey fragment samples.

This winter is the first they also have a permit in place to attach barbed satellite tags to specific SRKW individuals. A King 5 story on 1/25/12 suggested they do plan to deploy satellite tags during this cruise. The question of whether the risks of tagging exceed the potential benefits has split the local research and conservation communities, with Brad advocating it’s worth it while Ken Balcomb of the Center for Whale Research said it’s not.

PDF assessing NWFSC permit (among others)

Candice Calloway-Whiting’s case for not tagging: 1) Added risk of fatalities from infections; 2) interference with care-giving by older females

Huffington Post article quoting Brad’s practical rational for tagging: 1) refining where acoustic detectors are placed and 2) offering new habitat use information to the transboundary orca-salmon meeting in Vancouver this March.

If you’d like to follow the Shimada’s progress this winter, one useful tool is the real-time Automatic Identification Service (AIS) data that is available through sites like http://marinetraffic.com Today they zig-zagged up the coast at about 10 knots. The forecast is for rough weather tomorrow (Friday) night, so expect to see the Shimada run for the more-protected waters of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Update: Monday 2/20/2012 1:10 a.m. (Pacific time)

After returning to Seattle briefly, presumably to wait out bad weather on the outer coast, the Shimada heads back out into the Strait of Juan de Fuca and is passing Race Rocks around midnight or 1 a.m. Pacific Time.

2/20: Shimada departs Seattle & Salish Sea

About 5 hours later (~6:00 a.m.) J and possibly K pod calls are heard on the Lime Kiln hydrophones by Jeanne Hyde and Laura Swan. There aren’t many fixes from AIS in the interim, but around noon the Shimada is moving east near the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Shimada steaming east at 7-10 knots around noon on 2/20

Sometime during daylight hours on 2/20/2012, the NOAA team tagged a J pod whale (J26, or Mike) that returned its first location around 1800. Here is a NOAA web page where the tagging data from SRKWs will be shared — http://www.nwfsc.noaa.gov/research/divisions/cbd/marine_mammal/satellite_tagging.cfm — and the first track posted there:

First track of a J pod whale with a satellite tag

And here is a summary of the first tagging event in 2012 by Chris Dunagan of the Kitsap Sun.

Updates on Shimada ship tracks — 2/21-23:

Shimada track on 120221 at 1527 Pacific time

No AIS data are easily available for the 24 hour period between 15:00 on 2/21 and 15:00 on 2/22. Then the Shimada made a few passes within the Strait of Juan de Fuca between 15:00 on 02/22/2012 and 01:00 on 02/23/2012 (as shown in screengrab below).

Evening to midnight Shimada tracks on 2/22-23

Updates on 2/25/12:

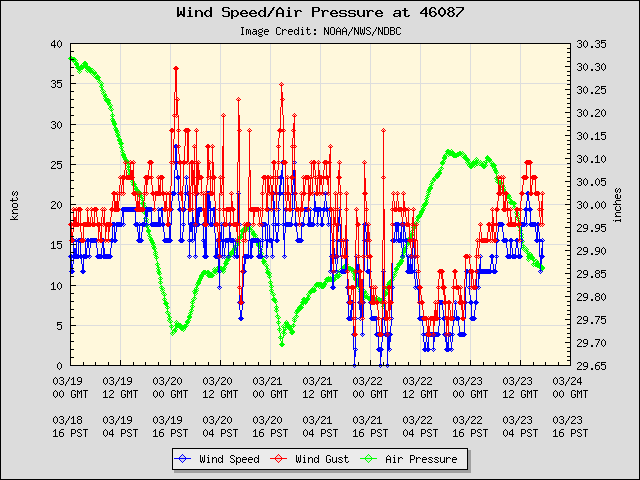

The Shimada arrived in Port Angeles around 10pm local time on Friday 2/24/2012 to escape a storm that brought 45 knot wind gusts to the mouth of the Strait of Juan de Fuca (see AIS screengrab and plot below).

Shimada runs for Port Angeles at 13 knots from 8pm local time on 2/24.

35 knot winds send the Shimada to port on 2/25

Updates on 2/27/12:

The highlighted text was changed in this 2/27 screengrab of the NOAA orca tagging web site. It indicates that the first tag provided data for only 3 days, though the group’s research permit states “Tags would be expected to stay attached for up to 25 weeks and are designed to release after one year.” What a drag for Mike that so little data was transmitted… At least he gave us an example of how far out on the shelf J pod goes, though (foraging?) at Swiftsure and La Perouse Banks is not new information.

3 day track of a J pod whale

The Shimada departed Port Angeles on 2/26/12 at 10 a.m. after weathering a storm. The latest track (below, as of 03:00 on 2/27/2012) suggests that after crossing the Strait of Juan de Fuca, the NOAA team moved north at 5-8 knots from False Bay at around noon. That could be a speed consistent with traveling killer whales, but no SRKW vocalizations were reported by humans on the San Juan Island hydrophones on 2/26/12 (though transient calls were heard at Lime Kiln around 17:00). The Shimada proceeded at those speeds until reaching the south arm of the Fraser River where they turned around at about 19:00 and increased speed to 8-10 knots. They passed False Bay going south at about midnight and then proceeded out the Strait of Juan de Fuca.

Shimada track for 2/26-27/2012.

Updates on 2/28/12:

The Shimada began a search pattern today, zig-zagging south along the outer coast of Washington at about 8 knots. The screengrab below shows their track from midnight until 4pm local time on 2/28/12.

Shimada track for 2/28/2012 00:00-04:00 Pacific time.

The weather forecast suggests they’re in for a pretty rough ride, though weather is expected to moderate on Wednesday:

PZZ150-290200-

COASTAL WATERS FROM CAPE FLATTERY TO JAMES ISLAND OUT 10 NM-

849 AM PST TUE FEB 28 2012

…GALE WARNING IN EFFECT THROUGH THIS EVENING… TODAY…SE WIND 25 TO 35 KT. COMBINED SEAS 7 TO 10 FT WITH A DOMINANT PERIOD OF 14 SECONDS. RAIN.

TONIGHT…SE WIND 25 TO 35 KT…BECOMING S 15 TO 25 KT AFTER MIDNIGHT. COMBINED SEAS 10 TO 13 FT WITH A DOMINANT PERIOD OF 14 SECONDS. RAIN IN THE EVENING…THEN SHOWERS AFTER MIDNIGHT.

WED…S WIND 15 TO 25 KT. WIND WAVES 2 TO 5 FT. W SWELL 11 FT AT 15 SECONDS…BUILDING TO 14 FT AT 15 SECONDS IN THE AFTERNOON. SHOWERS LIKELY.

WED NIGHT…W SWELL 15 FT. W WIND 10 TO 20 KT. WIND WAVES 1 TO 3 FT.

Oops. Looks like the turned back and as of Tuesday 2/28/2012 at 17:10 were searching in the more-sheltered Strait of Juan de Fuca –

Scant AIS data suggest Shimada returning to Salish Sea.

Updates Wednesday 2/29/2012:

Shimada patrols Strait from 2/28 19:00 to 2/29 08:24

Marinetraffic.com data show the Shimada criss-crossed the shelf at 6-9 knots from 17:00-22:00 on Wed 2/29/2012.

The Shimada slowed to 3-4 knots near Sooke around 8 a.m. on Wednesday 2/29. It is possible that the decrease in speed and changes of direction were related to an effort to observe the Bigg’s killer whales that were reported by Ron Bates on Orca Network’s Facebook page ~6-7 hours later: “T20 & T21 4.4 Nautical N.E of Race Rocks 1445.”

Siitech.com AIS data for 2/29/2012 show a search pattern in the Strait of Juan de Fuca. Speed begins is mostly ~6 knots, but slows to 3-4 during direction changes near Sooke and increases to about 10 knots during return to inland waters.

Graphical synopsis of the first 2 weeks:

The NOAA team seems to have been concentrating on the Strait of Juan de Fuca in its search for killer whales the last two weeks.

Shimada ship tracks for first 2 weeks of February 2012 cruise.

NOAA's search pattern in the Strait of Juan de Fuca

Updates on 3/2/2012:

On 3/1 Orca Network reported on their Facebook Page this notice from John Ford:

A J pod sighting from yesterday, sent by John Ford of DFO’s Pacific Biological Station:

We observed J pod southbound off Nanaimo at 1800 yesterday (2/29). They were heading (south) towards Dodd Narrows when we left them at dark.

Shortly afterwards the Shimada returned from the shelf and began patrolling Active and Boundary Passes.

Shimada track for Wed 2/29 @ 1800 to Thur 3/01 @ 1751.

Subsequently, they have been cruising in that area and Georgia Strait, mostly at 6-8 knots, but with one burst near East Point at 12 knots.

Shimada track 3/1 through 3/2 @ 09:22.